location: Firenze e Prato, Italy

Is fashion art?

This simple question conceals the complex universe of an articulated relationship that has long been investigated, but without arriving at a clear and unequivocal definition.Fashion – because of its need to be functional and thus refer to real life, but also its bond with craftsmanship and industry – seems to be far removed from the ideal of art pour l’art, a concept that nevertheless has not always been representative of the art world.Andy Warhol has taught us that the uniqueness of artwork no longer meshes with artistic production, and today we find a plethora of exhibitions by fashion designers, who in turn embrace the practices of contemporary art. In this context, can we still talk about the dichotomy between art and fashion as was the case in the 20th century? This project analyses the forms of dialogue between these two worlds:reciprocal inspirations, overlaps and collaborations,from the experiences of the Pre-Raphaelites to those of Futurism and from Surrealism to Radical Fashion.The exhibition itinerary focuses on the work of Salvatore Ferragamo, who was fascinated and inspired by the avant-garde art movements of the 20th century, on several ateliers of the Fifties and Sixties that were venues for studies and encounters, and on the advent of the culture of celebrities. It then examines the experimentation of the Nineties and goes on to ponder whether in the contemporary cultural industry we can still talk about two separate worlds or if we are instead dealing with a fluid interplay of roles. The unique aspect of the exhibition programme lies in the collaboration of several cultural institutions and the fact that it is being held at different venues.In addition to the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, promoter and organizer of the project together with the Fondazione Ferragamo, the various exhibitions are being hosted by the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, the Gallerie degli Uffizi (Galleria d’arte moderna di Palazzo Pitti) and the Museo Marino Marini in Florence, and by the Museo del Tessuto in Prato. These institutions took an active part in implementing this concept with the aim of inspiring joint reflection.

The emblem of the exhibition. It is a tribute to the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo that curated and conceived of the project and a symbol: on the one hand, a decorative element essential to the aesthetics of one of Salvatore Ferragamo’s models from 1958, the Tirassegno pump, and on the other a work by one of the great American artists of the second half of the 20th century, Kenneth Noland, who inspired it.

The exhibition curators. The exhibition project involved numerous people. The Museo Salvatore Ferragamo exhibitions has 4 curators: Stefania Ricci, Museo Salvatore Ferragamo Director, Maria Luisa Frisa, Enrica Morini, and Alberto Salvadori. Bringing in their varied areas of expertise and personalities, they worked day after day on the construction of this itinerary, along with the directors and staff of the different institutions that are participating in this initiative with great enthusiasm and spirit of collaboration and that worked with the authors of the catalogue, who helped the curators in the final choice of artworks, offering their knowledge and professional experience. There are numerous loans from the most prestigious public and private collections, both in Italy and around the world, giving this exhibition an International air.

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo

Across Art and Fashion

1. The Case of Ferragamo. The first section of the exhibition is devoted to Salvatore Ferragamo and his shoes, which were considered genuine works of art as early as the Thirties, in accordance with a concept of art focused as much on technique as on conceptual creativity. Ferragamo used the Renaissance artist’s bottega as the model for his work, and Florence offered myriad examples of these. Moreover, the shoemaker proudly embraced the role of the craftsman/artist central to Italy’s artistic tradition. A video installation shows shoes with their source of inspiration: the Classical world, the Orient, the avant-garde art movement of the nineteen hundreds and Surrealism, as well as the city’s culture of craftsmanship. This room also includes the original sketches for advertisements that the Futurist painter Lucio Venna designed in the Thirties for Ferragamo shoes, the styles created for intellectuals and artists and Kenneth Noland’s painting from the late Fifties that inspired Ferragamo for the decoration of a shoe and its name.

2. Fashion and Art inspiration. Art and fashion often play off of one another today and have done so in the past. While artists are fascinated by clothing as an essential tool for bringing realism to their creations, tailors have often taken inspiration from the world of art and acted like artists themselves. Art historians use the clothing in a painting to date the work of art and, vice versa, fashion historians use the clothing in paintings to study the way garments moved, how they were held and how they fell. The history of modern Italian fashion began with the very first debates at the turn of the 20th century on the need to give Italian clothing production a national identity, and referencing Italian art was seen as a way to distinguish Italian fashion significantly from the French fashion that prevailed at the time.

3. Shapes and Surfaces. For centuries, artists have depicted clothing down to the tiniest detail as styles have changed over time, leaving us with a visual history of movements, poses and tastes, as well as of the tailoring solutions, materials and decorations designed by nameless craftsmen and women. Artists have actively participated in this rivalry to create luxury goods, designing fabrics, laces, embroideries and even ballroom costumes and giving rise to what would become fashion communications with masterpieces in the art of engraving. During the eighteen hundreds, fashion was beginning to spread in the cities with the contribution of the textile industry and modern forms of commercial distribution. A complete transformation was seen, and new and original ways of interaction between art and fashion arose. The relationships between these two worlds grew closer and more intense with exchanges that were no longer limited to illustrating the upper class wearing the latest fashion. A series of examples is provided in this section to show visitors this interaction, which has now been taking place for over a century. It begins with the English Pre-Raphaelites and continues with the Viennese Secession of Gustav Klimt and Wiener Werkstätte, followed by Mariano Fortuny, without overlooking the experimental work of the Futurists. The section next explores the work of fashion-making artists like Sonia Delaunay and collaborative projects directly between artists and fashion designers, like Thayaht with Vionnet and Dalì and Cocteau with Schiaparelli, through to more recent collaboration. Specific attention is paid to the designers who, inspired by art, revolutionised fashion, such as Yves Saint Laurent with Mondrian. This theme is analysed from various standpoints: the artists who created alternatives to current trends and those who collaborated with the fashion industry; fashion designers who sought out artists’ creativity and shared the avant-garde ideas they found to be the most original, but above all found inspiration in artwork of all ages for shapes and surfaces.

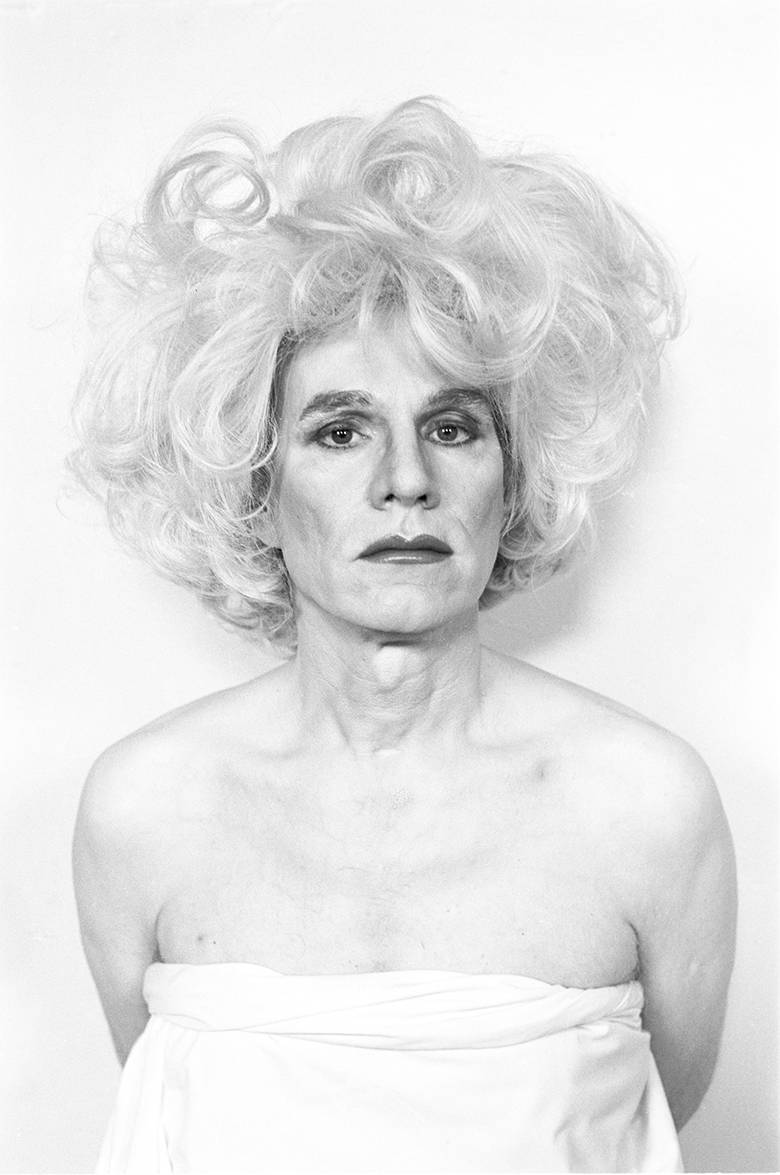

4. Andy Warhol, Communication Strategies. Artists have often collaborated with fashion communications, as illustrators for magazines and advertising catalogues. The work of Andy Warhol is one of the most famous examples of this symbiosis between the worlds of art and fashion. Warhol’s career began in fashion when, in the early Fifties, he worked as a commercial illustrator for Glamour, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, designing subtle, elegant shoes. This section will include pages published in fashion magazines of the time showing his first pieces as a fashion illustrator. Warhol also directed Interview, a magazine that straddled the worlds of art and fashion. 18 editions of Interview are shown here. With his presence on New York’s cultural scene, attending parties, opening nights, retrospectives and fashion shows, he helped shape the relationship between art, fashion and celebrities that we recognise today. This concept is explored in a series of photographs showing Warhol at various New York social events and with the Makos Studio’s famous installation Altered Image. There is no doubt that with his work, Andy Warhol unleashed high-impact - and frequently sacrilegious - aesthetic input, the most blatant example being The Souper Dress, a distillation of fashion, art and industry. Made in the Sixties out of paper, cellulose and cotton, with a silk-screen print of the famous Campbell soup can label repeating sequentially, this dress is on display as part of the exhibition.

5. Germana Marucelli, Rare Interpreter of Poetry. While Ferragamo’s atelier was modelled after a Renaissance artist/craftsman’s bottega, in which technique was as fundamental as creativity, Germana Marucelli’s atelier in the Sixties was a gathering place for fashion players, artists and intellectuals united in their search for new forms of expression that could interpret the spirit of their time. This section recreates Marucelli’s atelier/salon and shows the original works of art that hung on the walls, pieces by Pietro Zuffi, Getulio Alviani and Paolo Scheggi, along with the clothing created through the collaboration of these artists. Including documents, photographs, promotional brochures and publications, this section of the exhibition also documents the years leading up to this time, i.e., the post-war period, when the dressmaker established the San Babila poetry award, and writers and poets, including the most influential poets of the Italian 20th-century, like Ungaretti, Quasimodo and Montale, frequented her salon every Thursday.

6. From the Atelier to the Mood board. This section moves from the atelier to the mood board to show how fashion designers are increasingly storytellers through the images that emerge from a flow of information, as they seek to stimulate the public’s attention and memory. Produced thanks to A MAGAZINE CURATED BY, this space provides the public with the imaginary, visual universe of brilliant creative minds, like Haider Ackermann, Martin Margiela, Yohji Yamamoto, Iris van Herpen, Dries van Noten, Giambattista Valli, Stephen Jones, Rodarte, Jun Takahashi, Kris van Assche, Martine Sitbon, Proenza Schouler and Riccardo Tisci, in a kaleidoscope of art, music, poetry and photography.

7. Yinka Shonibare. Yinka Shonibare, a British-Nigerian artist, shows us that art can use fashion to shape its critical language. His installations, film transpositions, offer a profound reflection on multi-culturalism, mainly through the exploration of colonialism. The figures in his work are mannequins in theatrical, dramatic poses, dressed in the clothing of the 18th and 19th centuries, but made out of batik fabric, clearly of African origin.

8. Role-playing. Today, it is clear that the relationship between paintings art and fashion has overcome the dualism (in which two separate systems sum each other up and interact but remain distinct) seen in the history of fashion throughout the last century. Like art, fashion reflects on the practice of the craft, and through the work of artists like Hussein Chalayan, Martin Margiela, Viktor & Rolf, Helmut Lang and Nick Cave, this section demonstrates how it is increasingly difficult in modern times to define and classify the various modes of creative expression.

At the other museums

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze

Italian Periodicals of the20th Century

Connected to the fourth section at Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, the exhibition at the city’s national library shows how the relationship between art and fashion is depicted in the press, beginning with the early nineteen hundreds and focusing on Italy in particular. It includes the fashion illustrations published in magazines before the advent of photography to the work of avant-garde artists – the Futurists in particular – in the debate on clothing and the reassessment of craftsmanship in fashion. It goes on to explore the role that important names in fashion have played in fine art printing and art events and, vice versa, it also shows how fashion magazines have published articles on art exhibitions and other themes closely related to art, or even used artists themselves as models and spokespeople for fashion collections.

Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria d’arte moderna di Palazzo Pitti - Sala del Fiorino

The Fashionable 19th Century

It was in the 19th century, with the rise of the bourgeoisie and industrial production, when fashion ceased to be the privilege of the ruling classes and aristocracy alone, that the exchange between art and fashion intensified. In the paintings of the early part of the century, the focus on clothing coincided with the conception of taste extended to every aspect of living and of appearance, reflecting the democratic climate fostered by the French Revolution.Women dressed in linen and cotton, preferably white, contrasting the ornate ostentation of the ancient régime with an ‘elegance’ based on the light, essential and simple forms reminiscent of classical sculpture. In the mid-19th century portraiture became the pictorial genre destined to introduce the new principle of truth into art, turning to character studies and the meticulous depiction of clothing and the surroundings, in keeping with the style of the naturalist novel.In the second half of the 19th century, figurative art, along with the nascent field of photography, recorded cross-sections of reality corresponding to aesthetics increasingly aimed at capturing the observed subject in order to offer a true rendering. Artists viewed fashion as the sign of the new and dynamic modernity, and in their art works they emphasized details and accessories that acquire the mysterious power of symbol. The fashion of the period became endowed with an unprecedented professional structure (haute couture) that became the point of reference for a socially composite public of female consumers.With their art, painters such as Giovanni Boldini contributed to the growth of this phenomenon, striving to make the display of elegance and social optimism of the era as realistic as possible, in keeping with the effervescent climate of the Belle Époque and the aspirations of the middle class, which yearned for an International stage.

Museo del Tessuto of Prato

Nostalgia for the Future in Post-war Artistic Fabrics

In the nineteen hundreds, art, fashion and textile design intermingled and fed each other ideas, tones and styles that could be expressed through the new materials created by industry or discovered by experimenting in ateliers. A number of events helped them exchange ideas and grow, first the Monza Biennale expos (1923- 1930), followed by the Milan Triennale expos (from 1933 on), where artists and architects highlighted the need to give the decorative arts a function, a concept that is now considered an integral part of a design. This principle began to be applied in the post-war period when, as part of the necessary reconstruction, the reorganisation of Italian industry and flourishing arts movement led to interesting interactions between art, fashion and design. The IX to XI Triennale events in the Fifties served as crucial testing ground for artists and designers: Lucio Fontana, Bruno Munari, Roberto Crippa, Piero Dorazio, Gianni Dova, Fede Cheti, Fausto Melotti, Gio Ponti and Ettore Sottsass participated in the competitions that textile companies organised, presenting their designs – patterns for fabric prints – in a variety of colour schemes for clothing and upholstery in the modern home. Cultural events and initiatives like Carlo Cardazzo’s at Galleria del Cavallino in Venice, with special edition silk scarves designed by artists – wearable works of art – and tapestries – works of art for the home – bear witness to the mentality of applying aesthetics to daily life. In this section, the scarves of Edmondo Bacci, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Massimo Campigli, Roberto Crippa, Lucio Fontana, Bruno Saetti, Franco Gentilini, Emilio Scanavino and Marino Marini interact with the tapestries of Alfredo Chighine, Enrico Bordoni, Atanasio Soldati, Silvano Bozzolini and Guido Marussig, textile art that reflects the concept of Total Art embraced in those years.

Museo Marino Marini

Collaborations

The boundaries between art and fashion became less clear in the Eighties, when the forms of relationship between the two worlds grew on an International level. Art institutions opened their doors to designers, such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1983 with Yves Saint Laurent or the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence in 1985 with Salvatore Ferragamo. Saint Laurent and Ferragamo were the pioneers of an increasingly widespread trend that viewed the exhibition of a fashion designer’s work at a museum as a form of legitimation of his or her work.A new category of exhibition curators and dedicated museums emerged. While art galleries and auction houses paid more and more attention to the phenomenon, major fashion designers created spaces specifically devoted to art exhibitions and funded shows and artwork around the world, contributing to their growing fame. In turn, artists have collaborated with fashion for the most varied and complex reasons: from simple financial considerations to the desire for popularity, from personal relations to curiosity, and from the grand project of a total work of art to a revolutionary utopia. Salvatore Ferragamo represents an example of the collaboration between art and fashion, which is the consequence of a practice launched by the company founder in the Thirties.The themes of tradition, drawn from 10 the brand’s history, stimulate reflection on contemporaneity, moving beyond fields strictly related to fashion. Since 1996, when the fashion house supported the first Florence Biennale, “Il Tempo e la Moda”, curated by Germano Celant, Ingrid Sischy and Luigi Settembrini, and hosted a retrospective exhibition on Bruce Weber at the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo, which had just been inaugurated, the relationship with the art world has intensified. It got artists involved in communication projects, limited-edition pieces and works of art created especially for exhibitions and special events.

Window project

Riccardo Benassi, Every quote is a note, please reply In connection with the “Across Art and Fashion” exhibition, an art project involving the windows at the Salvatore Ferragamo flagship store in Florence will also be staged for the show opening. For this special event, Riccardo Benassi – artist, writer, performer, musician and designer – was chosen. He has created a new full-immersion scenario. Based on some of the words of artists and fashion designers from the past regarding the relationship between art and fashion, Benassi has created a continuous visual poem. The project proposes aesthetic unity among the window displays, as if this were a narrative facing the street and requiring the presence of passers-by in order to exist. Text becomes image and updates the famous quotations to bring them into the subjective experience of our everyday lives. This is why the artist has chosen to respond to the text with another text, to highlight the fundamental element of the dialogue between these two realms, but also – and Salvatore Ferragamo’s quotation evokes this – the dialogue between craftsmanship and philosophy of life. The choice of font, invented by Benassi and the sign of his presence in a given space over time, is fundamental here, as it interacts with the lighting, natural during the day and with strobe lights at night. Consequently, the material supporting the words has been selected because of its reflecting qualities. The work strives to create an emotional rapport not only with passers-by but also with the architecture hosting it.

Curricula

Maria Luisa Frisa Art critic and curator, Maria Luisa Frisa is a professor at the IUAV University of Venice, where she heads the Fashion Design and Multi-Media Arts program. She is the Editor of Marsilio Editori’s Mode series about ideas and forms in fashion. Her most recent exhibition was Bellissima. L’Italia dell’alta moda 1945- 1968 (Rome, MAXXI, November 2014-May 2015; Bruxelles, BOZAR, June-September 2015; Monza, Villa Reale, September 2015-January 2016; Fort Lauderdale, NSU Art Museum, February-June 2016). Her most recent book was Le forme della moda (Il Mulino, 2015).

Enrica Morini With a university degree in the History of Art Criticism, Enrica Morini has, since 1995, taught the History of Contemporary Fashion at the IULM University of Milan. She has published Storia della moda dal XVIII al XXI secolo (Skira, 2011) and essays on a number of topics, including ready-to-wear fashion, youth trends, Italian and French fashion and the connections between art and fashion. She has curated exhibitions on Italian fashion in the second post-war period, on the 60s and 70s and on women’s new role and way of dressing during the first world war. She works with museums and foundations specialised in the history of fashion and textiles.

Stefania Ricci A graduate of the University of Florence, holding a degree in the Humanities with an emphasis on Art History, Stefania Ricci began collaborating with the Galleria del Costume, Palazzo Pitti and with Pitti Immagine in 1984, overseeing the organisation of exhibitions and the publication of catalogues like La Sala Bianca: nascita della moda italiana (Electa) in 1992, in addition to the Emilio Pucci exhibition (Skira) for the 1996 Florence Art and Fashion Biennale. In 1985, Ricci curated the first retrospective on Salvatore Ferragamo at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and various stops along its tour at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (1987), the Los Angeles County Museum (1992), the Sogetsu Kai Foundation in Tokyo (1998) and Museo des Bellas Artes in Mexico City (2006), as she began organising the company’s archives. Since 1995, she has been Director of Museo Salvatore Ferragamo and oversees cultural events around the world. Since then, she has curated all the exhibitions organised by the museum and the exhibition catalogues, including Audrey Hepburn. A Woman, the Style (Leonardo Arte, 1999), Evolving Legend Salvatore Ferragamo 1928-2008 (Skira, 2009), Greta Garbo. The mystery of Style (Skira, 2010), Marilyn (Skira, 2012), The Amazing Shoemaker (Skira, 2013), Equilibrium (Skira, 2014) and A Palace and the City (Skira, 2015). She was named Director of Fondazione Ferragamo in 2013.

Alberto Salvadori studied Art History in Pisa, at Sussex University and Reading University, and specialised in European Modern and Contemporary Art in Pisa. He earned a Master’s degree in Curation from the Accademia di Brera and has filled research positions with the University of Pisa and the Getty Research Institute. After having worked at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin for two years, he managed the general catalogue of Galleria d’arte moderna di Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Since 2009, Salvadori has been Artistic Director of Museo Marino Marini in Florence and, since 2007, Director of the Cassa di CURATORS 12 Risparmio di Firenze Observatory for Contemporary Arts, for which he has co-produced and coordinated interdisciplinary projects covering art, music, cinema, dance and theatre. Since 2011, he has been a board member of the Istituzione Bologna Musei and, since 2015 on the board of the Polimoda fashion training institute in Florence and a member of the Amaci steering committee. Since 2009 to 2015, he has served on the Polo Museale Fiorentino commission for contemporary art acquisitions, donations and projects. Since 2015, he has curated the Decades section of the Miart art expo. In 2011, Salvadori curated the project on the new Brazilian art scene Tudo è for Fondazione Pitti Discovery. He has also curated several one-man shows in recent years, including Gio Ponti and Richard Ginori, Andrea Zittel, Joao Maria Gusmao and Pedro Paiva, Tony Lewis, Melotti guarda Melotti and Lynn Chadwick. He curated the show Dall’arcaismo alla fine della forma at Fondazione Iberé Camargo in Porto Alegre and the Pinacoteca di Stato in San Paolo, as well as a show on Marino Marini in Chicago. He has edited several publications: Catalogo Generale Collezione Iannaccone, Arte tra le due guerre, Milan, 2016; Catalogo Collezione Enea Righi, Palazzo Fortuny, Venice, 2016; Sulla Croce, Collezione Olgiati LAC Lugano, 2016; Teoria extraterrestre. João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva, Milan 2014; Andrea Zittel: Between Art and Life, Milan 2010; General catalogue. Palazzo Pitti Modern Art Gallery, Livorno 2008.

Riccardo Benassi is a visual artist born in 1982 in Cremona, Italy, who currently lives and works in Berlin, where he is an artist-in-residence sponsored by Artisti per Frescobaldi with the Künstlerhaus Bethanien. His art works are created through the complex assembly of images, texts, sounds, colours, design pieces and various materials that, together, form large-scale installations, videos, art books and sculptures in which the visual part is only one of the many elements forming the end result. He recently won the ArtLine public art contest in Milan with his piece Daily Desiderio, an ethereal bus stop featuring a LED panel on which the artist promises to send a text message a day, every day of his life. His pieces have been included in various public and private collections in Italy and abroad and have been shown in many institutions, including Museion, Bolzano; VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin; MAXXI, Rome; Macro, Rome; MAMbo, Bologna; Museo Marino Marini, Florence; Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle, Berlin; PAC, Milan; NCCA, Moscow; and OCAT, Shanghai. He recently published Lettere dal sedile del passeggero quando nessuno è al volante (Mousse Publishing 2010), Briefly, Ballare (Danilo Montanari 2012), Attimi Fondamentali (Mousse Publishing 2012), Techno Casa (Errant Bodies 2015) and Sicilia Bambaataa (NERO Publishing 2015). Riccardo Benassi teaches at the Accademia di Belle Arti Carrara in Bergamo and dBs College in Berlin.

Karmachina is a visual design studio established in Milan in 2013 combining the varied visual arts and multimedia experience of its three founders, Vinicio Bordin, Paolo Ranieri and Rino Stefano Tagliafierro. The studio creates multimedia projects that translate visual and sound experimentation and content and narrative technique research into absolutely original and highly artistic installations, video environments and multimedia journeys. In 2013, Karmachina took part in an audio-visual project inspired by the work of Armenian director Sergei Parajanov for the opening ceremony of the Golden Apricot Film Festival in Yerevan, commemorating ninety years since the director’s birth. In the same year, for the 31st annual Festival Internazionale di Musica in Portogruaro (Venice, Italy), the studio presented Kino Quartet, a video map exploring the relationship between Beethoven and 20th century visual arts. ARTISTIC INSTALLATION FOR WINDOWS VIDEO INSTALLATIONS 13 In 2014, it created BRAHMS WoO, a video map about Hungarian influence on the music of Johannes Brahms for the 32nd annual Festival Internazionale di Musica in Portogruaro. In 2015, it created the film/installation Devilish, the deed for the presentation of VIC MATIÉ’s fall/winter 2015-2016 collection. In the same year, it participated in the first In\visiblecities Urban Multimedia Festival in Gorizia, Italy with A heap of broken Images. Gorizia 1915-1918, a video map/opera on the Great War, accompanied by a live music performance by Teho Teardo. Also in 2015, for the 33rd Festival Internazionale di Musica in Portogruaro, Karmachina created Talea, a video map that translates the piece of the same name, by French composer Gérard Grisey, into images, for the performance by Names - New Art and Music Ensemble of Salzburg.

Silvia Cilembrini and Fabio Leoncini live and work in Florence, where they graduated in 1993 and remained, as “enthusiasts of matter,” assisting Professor Remo Buti of the Interior Design and Architecture program. From 2005 to 2008, Fabio Leoncini taught “Exhibition Design” as part of the Design program at the Architecture Department in Florence. As designers, they have collaborated with leading Italian and foreign companies and multinationals, designing projects around the world. Since 2001, they have designed the lay-out of many Museo Salvatore Ferragamo exhibitions, both in Italy and abroad, including 1928-2008 Evolving legend of Salvatore Ferragamo, which was first held in Shanghai and later at the Milan Triennale, where the architectural publication ADI awarded it the prestigious Compasso d’oro for 2009. In 2014, they founded Green Spirit, an ambitious ecological theme park, which has since become a prolific factory of ideas, solutions and projects for all facets of entertainment.

The exhibition curators.

The exhibition project involved numerous people. The Museo Salvatore Ferragamo exhibitions has 4 curators: Stefania Ricci, Museo Salvatore Ferragamo Director, Maria Luisa Frisa, Enrica Morini, and Alberto Salvadori. Bringing in their varied areas of expertise and personalities, they worked day after day on the construction of this itinerary, along with the directors and staff of the different institutions that are participating in this initiative with great enthusiasm and spirit of collaboration and that worked with the authors of the catalogue, who helped the curators in the final choice of artworks, offering their knowledge and professional experience. There are numerous loans from the most prestigious public and private collections, both in Italy and around the world, giving this exhibition an International air.

ongoing exhibitions:

Across Art and Fashion

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo

Florence

Palazzo Spini Feroni

19 May 2016 - 7 April 2017

Opening hours: 10 - 7.30pm Closed 1.1, 1.5, 15.8, 25.12

edited by

Maria Luisa Frisa, Enrica Morini, Stefania Ricci, Alberto Salvadori

Nostalgia for the Future in Post-war Artistic Fabrics Museo del Tessuto Prato

21 May 2016 - 19 February 2017

Opening hours: Tuesday - Thursday 10am - 3pm, Friday - Saturday 10am - 7pm Sunday 3pm - 7pm

Closed on Monday

Edited by

Daniela Degl’Innocenti Filippo Guarini Stefania Ricci

Layout design

Silvia Cilembrini, Fabio Leoncini