architect: Vittorio Garatti

location: Havana, Cuba

year: 19611964

Foreshadowing the Future

The National Art Schools complex, appointed National Monument of Cuba on the 8th of November 20121, embodied the spirit and principles of the Cuban Revolution, first victory of the broader Latin-American revolution, which covered the period of Simon Bolivar to that of Jose Marti, expression of the desire to create a large cultural centre of international socialism of Cuba and of Third World countries. The first investments made by the Revolution were in culture, with the conversion of the barracks into schools and starting up the “Literacy Campaign“, closing schools for a year and sending students to the villages to teach peasants to read and write. In this same period, the International School of Medicine and International School of New Cuban Cinema (ICAIC) were founded. All of these projects reflected the revolution in all its dynamic aspects. There were no set dogma, only total creative freedom. It was under these circumstances that the National Schools of Art were established, which Fidel Castro and Che Guevara decided to build in the most exclusive place of the Cuban bourgeoisie, the Country Club of Cubanacan.

This Cultural Centre for the Arts, was to accommodate the cultures of Asia, Africa and Latin America, in a spirit of integration and mutual interchange. The construction of the complex was a race against time, Cuba was at war and the work had to be completed as quickly as possible. The contract was initially entrusted to Selma Diaz, who, aware of the scope and enormity of the work, asked the more experienced architect Ricardo Porro, to tackle it. Porro understood its importance and owing to the time limitations, requested the collaboration of Vittorio Garatti and Roberto Gottardi.

“It was Porro himself, who we met in Venezuela, to call us in Cuba following the mass exodus of professors and technicians linked to the Cuban bourgeoisie, who, upon the triumph of the revolution, left the island. The universities had no professors, and soon after my arrival in December 1960, I was given a teaching assignment for an urban composition course“ (Vittorio Garatti).

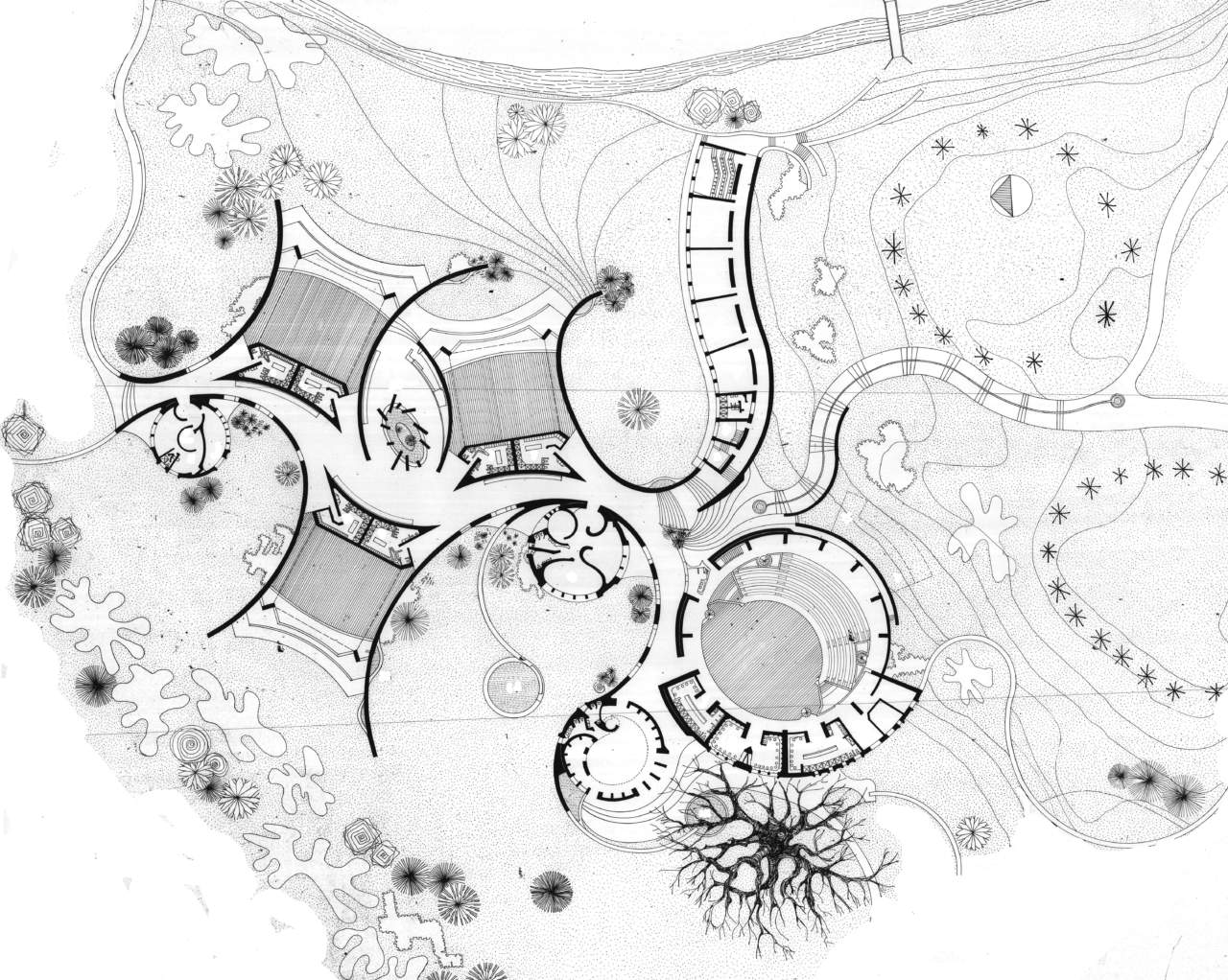

The five autonomous constructions of Modern Dance, Ballet, Music, Plastic Arts and Dramatic Arts, were located on the edge of the country club grounds, thus keeping the green area intact and constructing a “city-park“.

“On-site building began immediately after defining the ground plans. By day works were executed on site, by night the construction detail drawings were worked on to be executed the next day. I worked with the architect Jose Mosquera, at that time my first year student of Architecture, who supervised all phases of design and construction of the Ballet and Music buildings“(Vittorio Garatti).

The “formal“ result was not a “stylistic“ choice, but the result of a method of analysis of the “context“, understood not only as geographical, environmental and architectural but also social, cultural, artistic, literary, etc.

Art schools are permeated by the rhythm of the great Cuban musical tradition, by Wifredo Lam‘s painting, recognizable in the Ballet plan, by the poetry of Lesama Lima and the architectural elements typical of colonial architecture, like the “mid-point“ windows for the Ballet School, and by the principles of the Revolution.

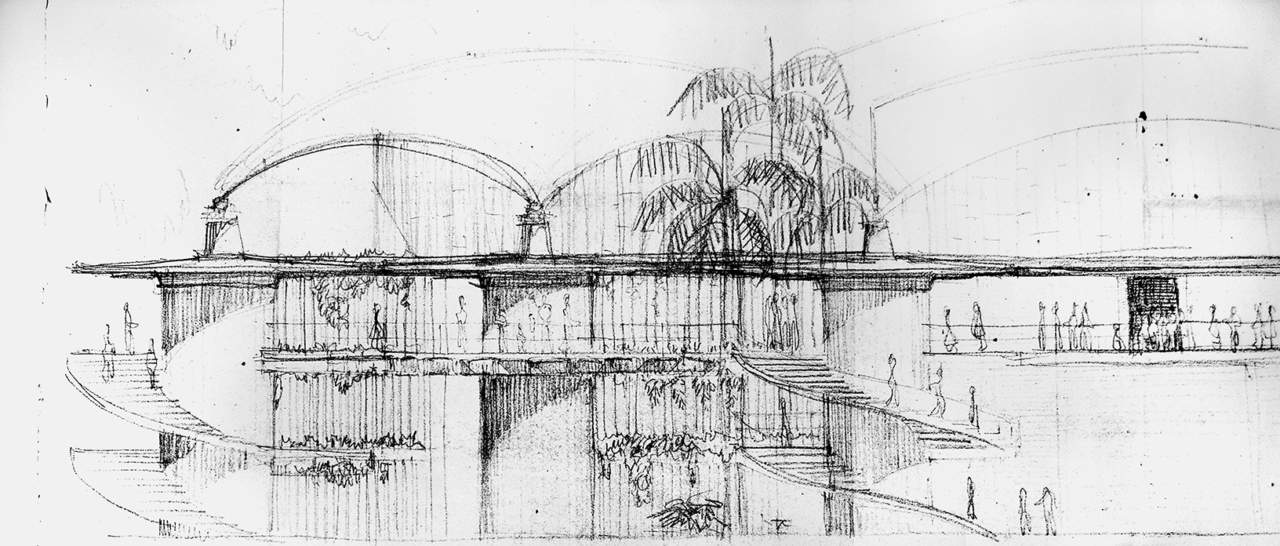

“In architecture, it is important to arrive at the forms as late as possible. They weren‘t meant to be“ forms of representation of power“. The revolution had placed power in the hands of the people, therefore, behind the people there were no longer masters to represent. There had to be architecture to experience and enjoy, spaces of freedom and of life“ (Vittorio Garatti).

The materials used were not chosen, at that time in Cuba there was little iron and little cement, there was no marble and stone was scarce, however, brick manufacturing was highly developed. “Working in a park, this “constraint“ imposed on building materials was a stimulus. Brick is perfect for gardens buildings. We only have to think of Arab gardens, the Arabian Nights, the British greenhouses in Alhambra. Drawing on our personal “museum of memory“, our references widened to Mediterranean gardens, the ceramics of Capri, the island of Panarea, the urban voluptuousness of Lansdown Crescent in Bath and domes of Labrouste library. It was a pure experience, in a climate of total creative freedom. There was much excitement and desire to create something new, something that belonged “to everyone“ and was “for everyone“. During construction one of the workers said to me; “first we built for others, now we are building for ourselves, we know that if our children have the potential, they will be able to go to this school. By constantly adding information to an open system, the latter changes and deforms according to different input it receives, thus triggering an organic creative process of “self-generating“ forms. If the process is authentic the product will be unrecognizable, often even by its very author, a new language that needs time to be understood“(Vittorio Garatti).

What are Art Schools today.

“In 2000, architect Sergio Baroni, with whom I built the Cuban pavilion for the international exposition in Montreal Canada in 1967, and the competition design for the monument for Playa Guiron, wrote the following about the future of Art Schools on occasion of the first registration of the Art Schools‘ course Watch of the World Monument Fund. (...)

For many years the National Art Schools have been much more than one of the most significant works of the revolutionary epoch; they have become an irreplaceable point of reference for everything creatively related to making architecture in Cuba

(...) the Schools of Art are not an “incident“, an episode, neither for the theme that they developed, nor for the place where they were built, but for the ability and the method used by their creators to create a complex where, in the extraordinary diversities of architectural solutions that they have produced, undoubtedly reaching the dimensions of a unitary discourse laden with quotations, allusions and metaphors, which make it particularly significant and communicative in terms of sensitivity.

(...) a new chapter is added to the now almost legendary Schools of Art: the new problem arises as to whether we should keep the initial programme or whether the schools should be adapted to new circumstances and needs. This is a frequent question in the re-functionalization of historical or archaeological works, that presents itself now as a problem of an unfinished contemporary work, and dedicated to such a dramatic function as arts education.

(...) Then there is the dilemma: is it a question of redeeming the memory of the country and world culture with a work of particular artistic value and significance, or of recovering and re-functionalizing the chains, in this case superior, to the country‘s education system?(Vittorio Garatti)2. Probably both. What is certain is that only by completing the project that was paralyzed in 1964, will it be possible to perceive the real cultural value and the enormous potential that the project already had from the moment of its conception. When the construction site was closed, only two years had passed since the missile crisis, and the situation in the country was totally uncertain. Cuba was still at war. The School of Ballet was 90% complete in 1964, missing doors and windows, the floors of the practice rooms and theatre, several facilities as well as furnishings. The situation for the School of music was different, which only reached 40% of its completion. There was no Symphony theatre, Chamber theatre, and the “gusanito“ which housed the service spaces, the library, the classrooms for the choir, in addition to the elevated walkway known as the “chain“, resembling a bicycle chain, which served as a connecting element of all these spaces, creating a central courtyard open to the park.

“I never ceased to tackle the completion project of the Art schools, a project never ends. A good architect should also be able to design the deformations that inevitably arise when one changes a system. But in the case of the Art schools there is no difference between “the project of today and that of yesterday“. It is the same project brought to a head. We completed, and here we preview, the virtual reconstruction of the School of Ballet and Music, so that we can renew that image which, over time, was fading, revealing the spaces as they will be once completed“ (Vittorio Garatti).

Music and ballet have suffered particularly from this state of incompleteness, but nevertheless they have welcomed some of the most famous contemporary Cuban artists in the world, such as Kacho, Rene Francisco, Sandra Ramos and many others, who today return to exhibit their work, with that yearning to return to their homes after a long journey. They have hosted and continue to host many contemporary artists, such as Spanish choreographer Miguel Rubio, who in 2008 performed the show “man_go“3 in the School of ballet, using for the first time its theatre of choreography, exploiting the full potential that the space offered him. For many years they have been used for exhibitions and displays linked to the Havana Biennial of Art, the subject of documentaries and films, and have never ceased to host and produce art. Their unique position at the centre of the Caribe makes Art schools a potential reference point for Cuban, Latin American and international art and culture in an historic time of great change, triggering an educational and economic process both nationally and worldwide. Starting up the old kilns for the production of terracotta not only ensures the future maintenance of the buildings at relatively low costs, but would serve to preserve and revive a forgotten building technique of our country, terracotta and Catalan vault. As Hugo Consuegra wrote, “(...) caught between an economic blockade and armed aggressions, Cuba can afford the luxury of building (...) Art schools of such proportions never before seen in London, Paris, New York or Rome“4. Today, that luxury must be put to good use, a large potential for a country that has in its culture, art, music, dance, cinema and literature, characteristics that distinguish it internationally. After all, as Ricardo Porro put it, “Architecture is a poetic frame for human life“.