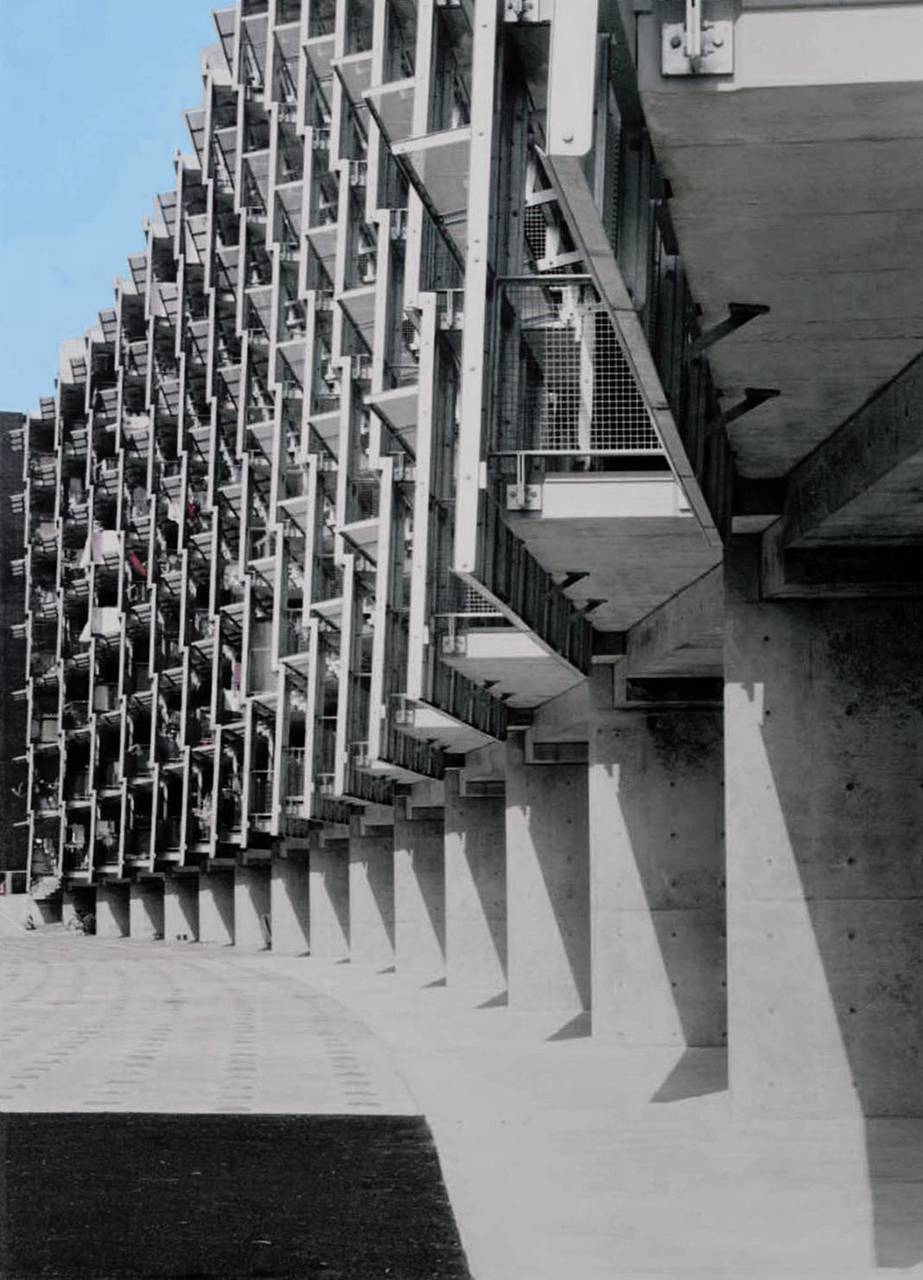

School of American Ballet, New York, 2006 - photo by Iwan Baan

Rome, November 7th 2009

Guido Incerti: We already know that if we were to ask you whether you are, or feel, more of an architect or artist, you would answer ”artist ” to an architect and ”architect ” to an artist. And so we will go straight to the second question. Today the border between architecture and art is becoming blurred. Do you think that, after the figure of the archi-star,

we will witness an assertion of the figure of the ”archist” or the ”artistect ”?

Liz Diller: I like these definitions, but I don’t think that is going to happen. Our culture has not completely absorbed this phenomenon of hybridizing in spite of the fact that one has fought against these limits throughout the 20th century. And today we are no longer the only ones who integrate media elements in our work. The real problem, with regard to this issue, is the institutions, or rather the way in which they are structured. In fact, they are never architectural-artistic institutions, or vice versa. Even in museums the disciplinary plan of architecture is separated from that of painting, which is indeed in its turn separated from sculpture. After all, there are countless artists who work with space and architects who are dealing with multimedia projects, but there is always a tendency to stress this division. It is hard to have to fight against these definitions, but that’s how it is.

Margherita Caldi Inchingolo: Thinking of the past, as for instance the Renaissance for instance, there were eclectic figures as Leonardo and Michelangelo. Today, on the contrary, rather than appreciate this attitude, one tends to cage an architect or an artist within a definition, why is this?

L.D.: I think it is due to the fact that our world has been profoundly professionalized, this makes the distinctions even clearer. And this is perhaps even more marked in America than in Europe and in the rest of the world. To give you an example, when one draws up a contract for a customer it is necessary to provide for lawyers and more lawyers, and everything is so highly specialized that it is also necessary to involve consultants, and sub-consultants.

G.I.: Can artists as Olafur Eliasson who interact closely with space, or Ben Rubin who in the specific works with mathematical spaces, be considered architects?

L.D.: I would say there is a current which embraces both disciplines. Architectural and artistic at the same time. Olafur is a perfect example of this, he has a firm which employs numerous professionals, just like an architect, and he is able to conceive the space in an experimental way, as few architects can. On our part we accept challenges without asking ourselves about their artistic or architectural origin or definition. There is no distinction to us, the borders are not clear. We throw ourselves into the next challenge, whatever it is, regardless of which field it belongs to. I think the greatest problems, in our case, are the consequences of the expansion of our firm. Everything has become more complicated, especially on a legal level. When the investments grow, you are working in a stable structure with guarantees, you have to support people. At the moment the archi-stars are in the centre of attention, but this is not due to a cultural fact, many developers are interested in the brand of these architects, today more than ever. However, we have the fortune of doing what we like, if something should bore us, we wouldn’t do it.

G.I.: Sometimes precisely the law prevents the project from being realized, as in the case of your installation at the last Biennial.

L.D.: It is an interesting process, sometimes one is forced to learn new things to get around obstacles we did not know existed. You have to rethink the project to find a solution. That makes you go beyond your limit, and discover abilities you did not know you possessed. Half of the work consists of solving problems, the other of creating them. I like to keep this balance. And we sometimes also try to solve problems we create ourselves.

M.C.I.: Why is this artistic aspect always underscored when someone speaks of your firm?

L.D.: We have worked with space from the beginning, but as usual the problem is not the definition. When the public opinion has realized that our projects were not buildings, and feeling the need to define them, it has defined them artistic. On our side we have never adopted a defensive attitude, we feel at ease with this ambiguity, that is how feeble the borders are.

G.I.: Many architects, as for instance Rem, use media extensively in their work, but unlike you they are in any case considered and defined as architects.

L.D.: This is a very strange phenomenon, we have never stopped to analyze it. In the early stages of our career we have been seriously criticized by the professionals, then we have suddenly enjoyed the approval of the category: a few months ago we won this prize (the (AIA Institute Honor Awards ’091). All these persons, in suits and ties, the same who had criticized us, have given us this recognition. Perhaps there seems to be a kind of resistance on our part. Rem, on the contrary, has always been linked to the world of architecture, he has written books, theorized, designed cities. It is probably just that the public opinion associates us with artistic installations, which we, on our part, continue to produce.

G.I.: Has it been hard to find customers, especially in the beginning of your career, and above all with this reputation of being artists?

L.D.: It is strange, because we really have never had to look for them, and perhaps we would never have found them if we were forced to do so. It has been just luck. I think we owe a great deal to a lot of people, first of all Isozaki, who contacted me in the Eighties, asking me if I wanted to design homes in Japan (the Slither Housing of Gifu). He was looking for four women to design the Master Plan of this area, inhabited principally by women. We have never thought of what might have happened afterwards. The next opportunity was the Slow House. An art collector came to us after a meeting with Steven Holl and Todd Williams. It was precisely Todd who mentioned our name during this meeting. In fact, during the interview the collector asked him who was his favourite architect, the one he appreciated. Todd said Liz Diller & Ricardo Scofidio without realizing that that question was a polite Japanese way of saying that he would not have given him the assignment, and that he was looking for someone else. And so he immediately came to us. The following event which gave us a real break was when we won the MacArthur Prize. This is a very important prize in America, you win a monetary fund for five years, like a study grant. And to us, in 1999, it was a lot of money. We were the first architects to receive it, Venturi has not won it, Eisenmann has not won it, and this has been a sign of approval for us and for our work, which has been awarded for the way in which we link architecture to culture in general. The foundation does not want to reward professionals who only exercise their profession, but someone who goes beyond its borders. After this recognition we began to receive important commissions, as the ICA and the success of the Eye Beam. Nothing has been planned, if it had been, it would never have gone like this. We have been very lucky, we have always taught and we have always been independent and free to choose.

M.C.I.: What is your opinion about exhibition spaces for art in the future, what will such spaces be like? Will they be museums, virtual spaces? Will our culture always need building-icons? Or perhaps we should rather ask whether this phenomenon will come to an end?

L.D.: We have never believed much in the discussion on the role of architecture in museums as compared to art, it is not in the foreground, it is not in the background but should, in our opinion, cooperate. It is different in Europe, one tends to sponsor culture, this has not happened in the United States. Culture has been based on private sponsors for many years, museums are created thanks to donations, and they are controlled by these donors. And everyone wants a museum by Piano, it is a status symbol. Obviously, Renzo Piano is a great architect. But it is as if they don’t look any further, in their search for new contributions, it is typical of the American mentality to choose the trophy architect.

We have been involved in a project for a museum, after the economic crisis, but there are no ambitions, as the only rule is to survive. And so we see a lot of institutions, also the biggest ones, so absorbed in rethinking their mission. In any case, we have also been involved in another initiative, to rethink an institution in such a way that it may be economically sustainable, and for this to be achieved there must be a cooperation between commerce and culture. It is probably the way to allow the institution to avoid being forced to make spectacular shows. To achieve a lot of visibility and thus spectators, the institutions have to stage spectacular shows, neglecting experimentation and research, not giving young artists an opportunity to try new paths and curators to experiment new strategies. But I think that there will be step ahead, and in spite of this culture will survive, because there is always patronage. A patronage which contemporary art always seeks, and to which it tries to cling, even if a lot of this art is highly ephemeral. So ephemeral that it is impossible to comprehend the contribution of multimedia relations within contemporary art, and that it is hard to appreciate its value. And everything has a lot to do with the direction contemporary art is headed towards. You know, paintings are always very reliable, but when you make multimedia works they often sound ”false”.

G.I.: Thinking of the future, perhaps the museums themselves will become ready mades, perhaps one will build a museum which contains the Guggenheim, considered a work of art.

L.D.: I hope that will not happen, the planning of an exhibition space is a true challenge for an architect. Especially if it contains contemporary works of art. Architecture is already old, what is contemporary is old by definition, and so the problem is how to assure the venue always remains up to date. I believe one must introduce the concept of transformable building. Their identity lies precisely in the fact that they can be transformed and thus brought up to date at any moment, capable of changing and adapting to every situation.

Another problem concerns the institutions, how can they be preserved? Part of the problem is the lack of public, children don’t go to museums, and so the future generations will go there less and less...Architects should understand that the spaces of museums have changed, they should make them more social, interactive, make the institutions step down from their pedestals, so that these spaces may be more involving. I think this is a correct way to design. Unfortunately there are also economic problems, which cannot be solved by the architects. Even as we speak, there are millions of museums, which are however created for tourism, a market which produces revenues, due to which many venues are created especially for this purpose.

G.I.: Perhaps the museums of the future will be in the web, there will no longer be any need for walls, and so we could also save materials and energy. The screen itself will serve as canvas.

L.D.: I think that is too simplistic, the screen is limited. I think there has been a moment of euphoria for technology and the Internet. According to this moment, no-one would need to travel, make love, or go shopping any more. In actual fact the Internet is just another means of expression, it has obviously amplified the possibility to do research considerably, but it is in any case limited. I think the introduction of art in the community is something that cannot be replaced. In fact, the screen is an individual experience which does not allow a critical confrontation with other people.

Notes:

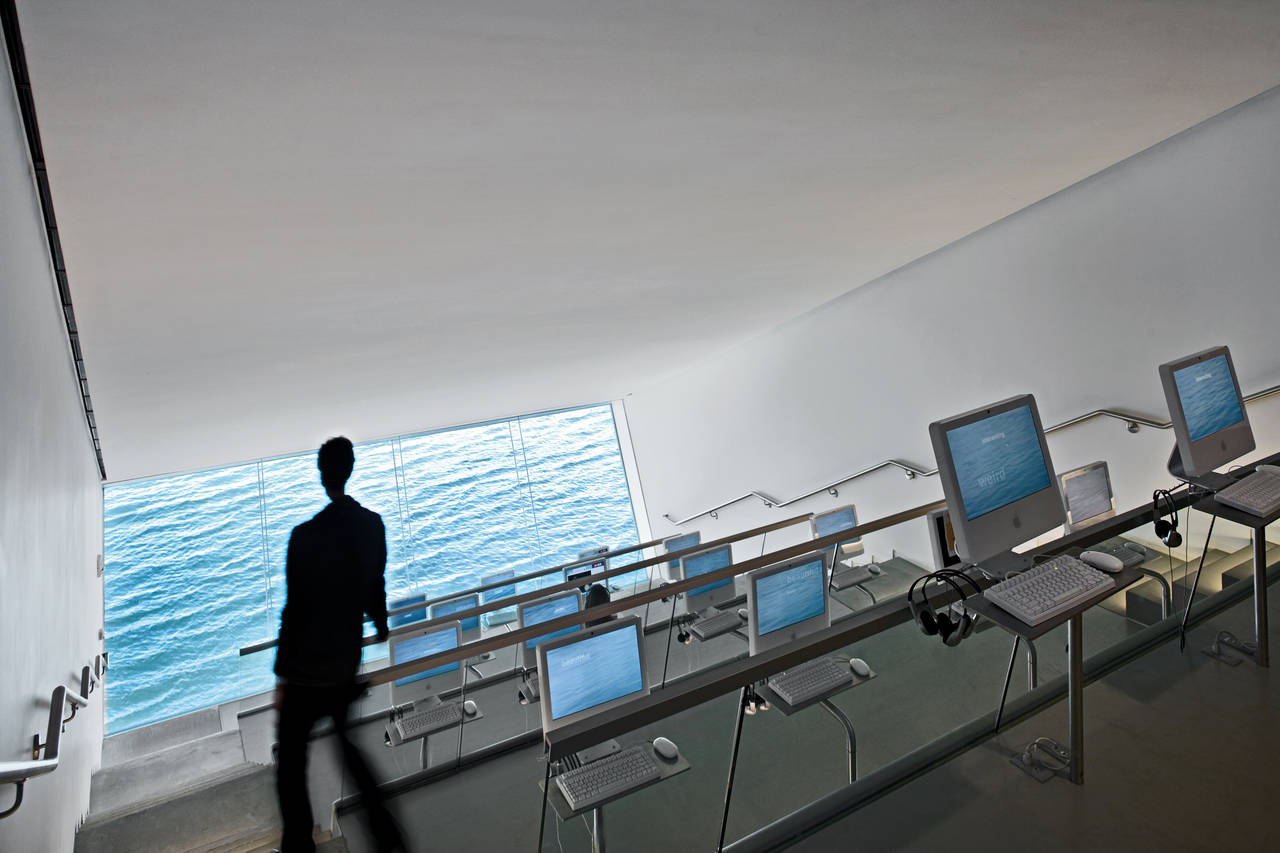

1 The American Institute of Architects (AIA) has officially announced the winners of the AIA Institute Honor Awards 2009, a prize assigned every year to outstanding figures in design, for the categories ”Architecture ”, ”Interior architecture ” and ”Urban and Regional Planning”. Diller Scofidio + Renfro have won in the Interior Architecture category with the project ”School of American Ballet ”, New York City.

Diller Scofidio + Renfro is an internationally renowned interdisciplinary design studio based in New York City. For three decades, we have realized work of civic and cultural significance through a practice that uniquely straddles a myriad of design disciplines (urban, landscape, interior, product, exhibition), media oriented installations, graphics, print, and experimental dance and theater productions. Elizabeth Diller Ms. Diller is a founding member of the studio and Professor of Architecture at Princeton University. Born in Lodz, Poland, she attended The Cooper Union School of Art and received a Bachelor of Architecture from The Cooper Union School of Architecture.